The Supreme Court has issued a decision ruling that there is no confusing similarity between the respective marks of Lacoste S.A. (“Lacoste”) and Crocodile International Pte. Ltd. (“Crocodile”) based on the Dominancy Test and the parties’ co-existence in other jurisdictions.

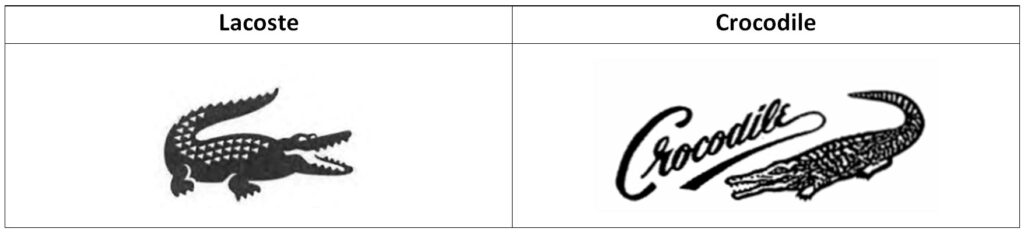

Lacoste is the registered owner of the “Crocodile Device” mark, while Crocodile is the applicant of the “Crocodile and Device” mark. The parties’ respective marks are depicted as follows:

Lacoste filed on 18 August 2004 an opposition against the application of Crocodile’s mark alleging that the latter’s mark is confusingly similar or identical to its “Crocodile Device” registration. As the registered owner of the “Crocodile Device” mark, Lacoste argued that it has the exclusive right to use the same to the exclusion of others and that it would be greatly damaged if the “Crocodile and Device” mark ripens into registration.

Crocodile, in its defense, argued that the two marks have substantial differences in appearance and overall impression. Crocodile explained that Lacoste’s mark is only a crocodile device facing the right, while Crocodile’s mark is a composite mark consisting of the stylized word mark “Crocodile” above the representation of a crocodile facing left. Moreover, Crocodile highlighted that both marks are concurrently registered in different countries, which contradicts Lacoste’s claim that there is confusing similarity between the two marks.

In its decision, the Supreme Court ruled that there is no confusing similarity between the two marks and used the Dominancy Test in explaining its ruling. Particularly, the Supreme Court made the following justifications supporting its ruling that there are distinct visual differences both in appearance and overall commercial impression between the two marks:

- Lacoste’s “saurian” figure is facing to the right and is aligned horizontally, while Crocodile’s “saurian” figure is facing to the left and the stylized word “Crocodile” is tilted in such a way that the right side’s alignment is higher than the left side; and

- Lacoste’s “saurian” figure is solid, except for the crocodile scutes on the body and base of the tail depicted in white inverted triangles, with crocodile scutes protruding from the tail of its “saurian” figure, while Crocodile’s “saurian” figure is not solid and is “more like a drawing”, which does not have crocodile scutes and is instead depicted with various scale patterns from the base of the “saurian” figure’s head to its tail.

Agreeing with Crocodile’s argument, the Supreme Court further explained that the foregoing differences are bolstered by the parties’ co-existence in other countries showing that there is indeed no confusing similarity between the two marks.

Aside from the issue on confusing similarity, the Supreme Court took the opportunity to rule on Lacoste’s allegation of trademark dilution. The Supreme Court ruled that there is no trademark dilution and Lacoste’s allegation is merely speculative for lack of sufficient basis. Lacoste was not able to present sufficient evidence to show Crocodile’s capacity to tarnish or intent to tarnish Lacoste’s mark and that Crocodile’s mark falsely suggests a connection with Lacoste’s mark to blur the distinctive quality of the latter.

As a final note, the Supreme Court ruled on the admissibility of “The Project Copy Cat” in relation to its jurisprudential value. In its opposition, Lacoste presented an expert witness from Consumer Vibe Asia, Inc. to explain “The Project Copy Cat” to the Philippine Intellectual Property Office-Bureau of Legal Affairs. “The Project Copy Cat” was a privately commissioned logo test conducted among four hundred fifty (450) respondents for Lacoste and Crocodile, which found the “saurian” feature a distinctive feature of both parties’ marks.

The Supreme Court determined that “The Project Copy Cat”, as consumer survey evidence, does not have probative value for failure to establish its trustworthiness based on the following factors that should be considered in determining the reliability of consumer survey evidence from the Manual for Complex Litigation:

- The universe was properly defined;

- A representative sample of that universe was selected;

- The questions to be asked of interviewees were framed in a clear, precise and non-leading manner;

- Sound interview procedures were followed by competent interviewers who had no knowledge of the litigation or the purpose for which the survey was conducted;

- The data gathered was accurately reported;

- The data was analyzed in accordance with accepted statistical principles; and

- Objectivity of the entire process was assured.

The Supreme Court elucidated that, based on the foregoing factors, Lacoste was not able to establish the requisite factor of trustworthiness.

Accordingly, Lacoste’s opposition was denied and Crocodile’s trademark application given due course.